According to the World Bank, around 20% of global water pollution is caused by textile processing, making it the second biggest polluter of freshwater resources on the planet. And with the ever-growing demand for fast fashion from our high-street retailers (and our consumption of clothing is only set to rise by 60% by 2030), we need to initiate the need for a dramatic change in the way that we produce and process clothing.

A report released by the Changing Markets Foundation has found that factories producing viscose in Indonesia, China and India have been operating under questionable working practices, and highlights the environmental and social impact of the production of this fibre.

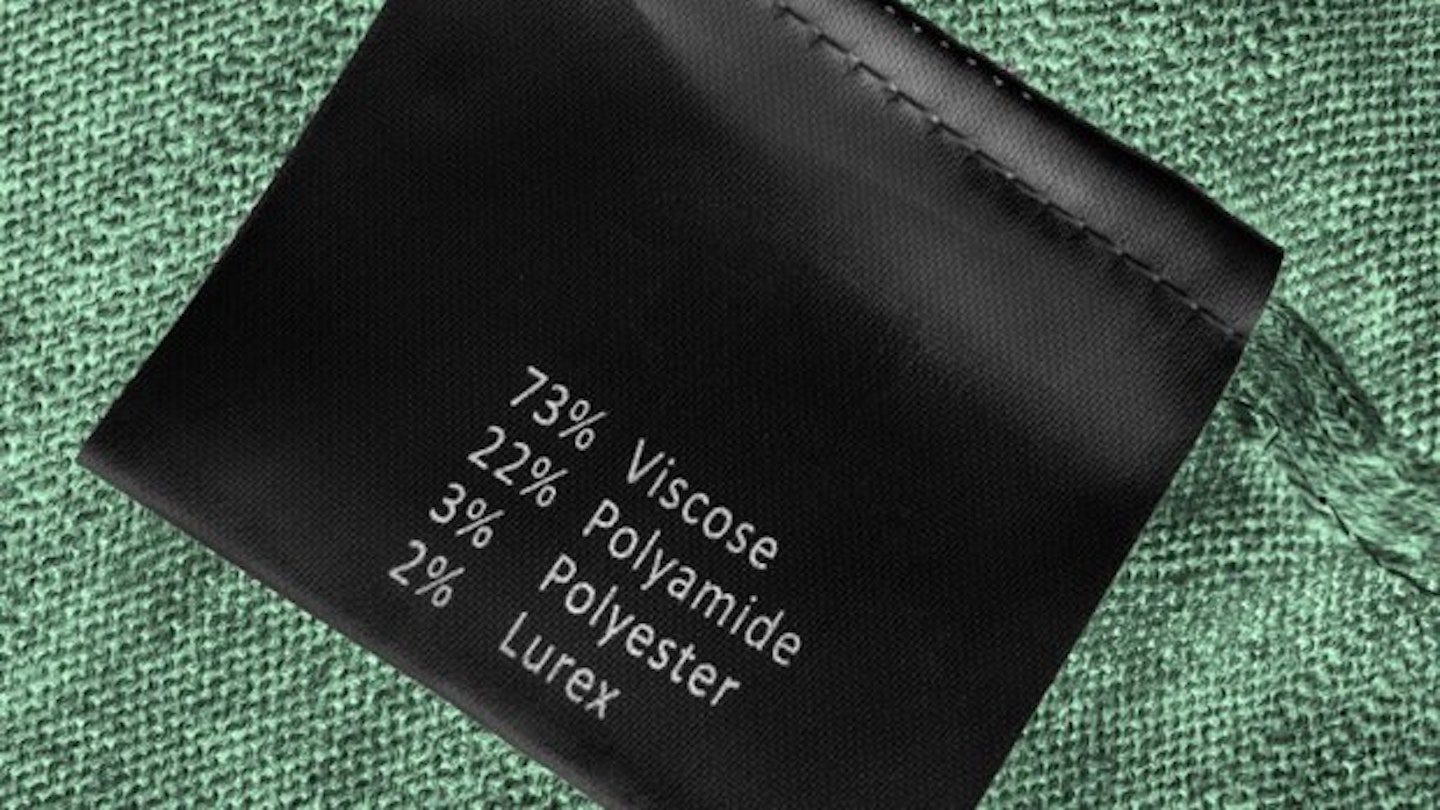

Whilst viscose, a man-made cellulose fibre derived from wood pulp, is said to be a more sustainable and ethical alternative to materials such as polyester or cotton, it often isn’t due to its prevalent production methods and ‘toxic run-off’ which has been found to be contaminating local water supplies and increasing the chance of major health risks for those that work to create and manufacture this fibre.

The report explains that, ‘because it is made from trees, and is therefore of ‘natural’ origin, viscose is categorised as a semi-synthetic fibre, which sets it apart from fully synthetic fibres such as polyester and nylon, which are derived from petrochemicals (e.g. oil). However, the ‘green’ label which fibre producers and clothes retailers routinely hang on viscose, is often very misleading and ignores the chemically intensive and highly polluting methods still used to manufacture this most versatile of materials.’

The report goes on to explain how the production of this fibre has quite a chequered history and how viscose rayon has a reputation of causing severe human health impacts as a result of the chemicals used to produce it. In the report, a quote from Dr Paul Blanc, someone who has meticulously researched the history of viscose, states that ‘throughout most of the twentieth century, viscose rayon manufacturing was inextricably linked to widespread, severe, and often lethal illnesses among those employed in making it.’

Additional problems in the manufacturing of this fibre have been caused by the increase in popularity of the ‘fast-fashion’ industry, which has transformed the production processes and consumption rates of our clothing. Whilst traditional fashion brands only release two collections a year, many high-street retailers are releasing between 16 to 20 collections a year and the effect of this is undeniable in terms of the amount of waste being generated at both the production and ‘post-consumer’ end.

Many of us that have bought clothes from these types of ‘fast-fashion’ retailers have probably remarked at how clothing is no longer made to last in the same way that vintage clothing did, and this is in no small part due to the reduction of quality and durability of products that are being churned out in order to meet consumer’s expectations. And think about it, how often do we go online and browse the 'new in' section of our favourite clothing websites only to be disappointed that there aren't any new styles since we last checked two days ago?

Another interesting point raised by this report is how in order to keep production costs down, the fashion industry has started to outsource production to cheaper places in the Global South, which offer both poorly protected workers and lax environmental standards. And this is an overriding issue with fast fashion, that this industry often places overwhelming pressure on workers in increasingly poor conductions to produce faster and faster in decreasing time constraints.

In an interview with the Retail Gazette, Changing Markets campaign manager Natasha Hurley said, ‘cheap production, which is driven by the fast fashion industry, combined with lax enforcement of environmental regulations in China, India and Indonesia, is proving to be a toxic mix,’ she then adds ‘with water pollution increasingly being recognised as a major business risk, shifting to more sustainable production processes should be high on retailers’ agendas.’

This report dramatically highlights the need for us to call for enhanced transparency and traceability throughout textile supply chains, as with transparency hopefully comes more accountability and responsibility for retailers and increased consciousness and awareness from consumers.

You might also be interested in:

Quick Links To All The Most Ethical Lines On The High Street

Katherine Hamnett's 'Choose NHS' Slogan Tee Is One We Can Get Behind

Follow Tara on Twitter @TaraPilks

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.