It’s fashion week. And in keeping with tradition, last week there was a reception at Downing Street to kick things off. However, this year things were a little different because for the second time in our country’s history we have a female Prime Minister. This shouldn’t be a remarkable fact, unfortunately it is. As such, what Theresa May wears is the subject of much discussion and what she does during this fashion week will be of huge interest to a few and moderate interest to some.

In recent years the reception has been hosted by the Prime Minister’s wife, Samantha Cameron in partnership with the British Fashion Council. This year it was hosted by Theresa May, or was it?

The invitations said that Theresa May was hosting the reception however her press officers were incredibly keen to stress that she was not hosting but ‘attending’ the event. I don’t know about you but I tend to think of myself as a host and not an attendee when I’m attending a party at my own house. Margaret Thatcher hosted a similar event in 1988so why the semantic struggle this year? The British Fashion Council were equally reluctant to confirm whether or not May was ‘hosting’ the event, despite what the invitations said, and instructed me that press releases would only be sent out after the event.

Why all the fuss or, rather, lack of? Perhaps our new Prime Minister is keen not to appear to take too keen an interest in fashion. Particularly at a time when she is overseeing Brexit and, rather controversially, attempting to bring back grammar schools. In many ways the PM is damned if she does and damned if she doesn’t. If she didn’t put thought into what she wore or dressed ‘plainly’ she’d be accused of all sorts and poked fun at just as Hillary is for her pant suits. But, on the other and equally less appealing side of the coin, because she evidently takes an interest in fashion – from leopard print shoes to £1, 395 Roland Mouret dresses she is labelled as a ‘fashionista’ and forced to shoulder the frivolous connotations that come along with that. As the Guardian’s former fashion editor Hadley Freeman says a woman can commit no greater crime than openly declaring an interest in fashion. Doing so is a lifelong invitation for people to belittle, undermine and dismiss anything you say thenceforth.

Politics, at all levels, has a complicated relationship with fashion but arguably what this really comes down to is gender. Our natural distaste for women who take an interest in fashion and dismissal of them is illustrative of the sexist hypocrisy which many women still navigate in their day to day lives. Men who present themselves well, by and large, are not subject to the same scrutiny.

‘You like clothes…don’t you Vicky?’ the leading question dangled in the stagnant air of the too small office in Westminster for an uncomfortably long period of time. The interrogator was a senior female Member of Parliament. At the time I was a 19-year-old intern. I didn’t really know how to respond. Was I being accused of a crime? Was this a trick question? Was I wearing the wrong thing?

I’d be lying if I told you that I could remember what my answer was but this incident has stayed with me for nearly ten years. After years of working in or reporting on politics my sartorial choices have been interrogated more times than I can recount, often by men of a certain age who would comment on my attire and then chortle in a self-congratulatory way that would make even my ‘did you buy those jeans like that’ dad cringe. However, it was the implication of this loaded question which made a particular impression on me.

The suggestion was that it had been noticed that I ‘liked’ clothes and that, in liking them I was somehow giving off a signal that there wasn’t enough room in my brain to be interested in anything else. Politics and fashion are not comfortable bedfellows although they do like the occasional snuggle. Politicians want to be taken ‘seriously’ at all costs (and there’s no denying that female politicians are forced to navigate a minefield every day in all they do) while fashion is, ultimately, about appearances and because of this it has long been fair game for pseudo-intellectual snobbery and wrongful accusations of air headedness.

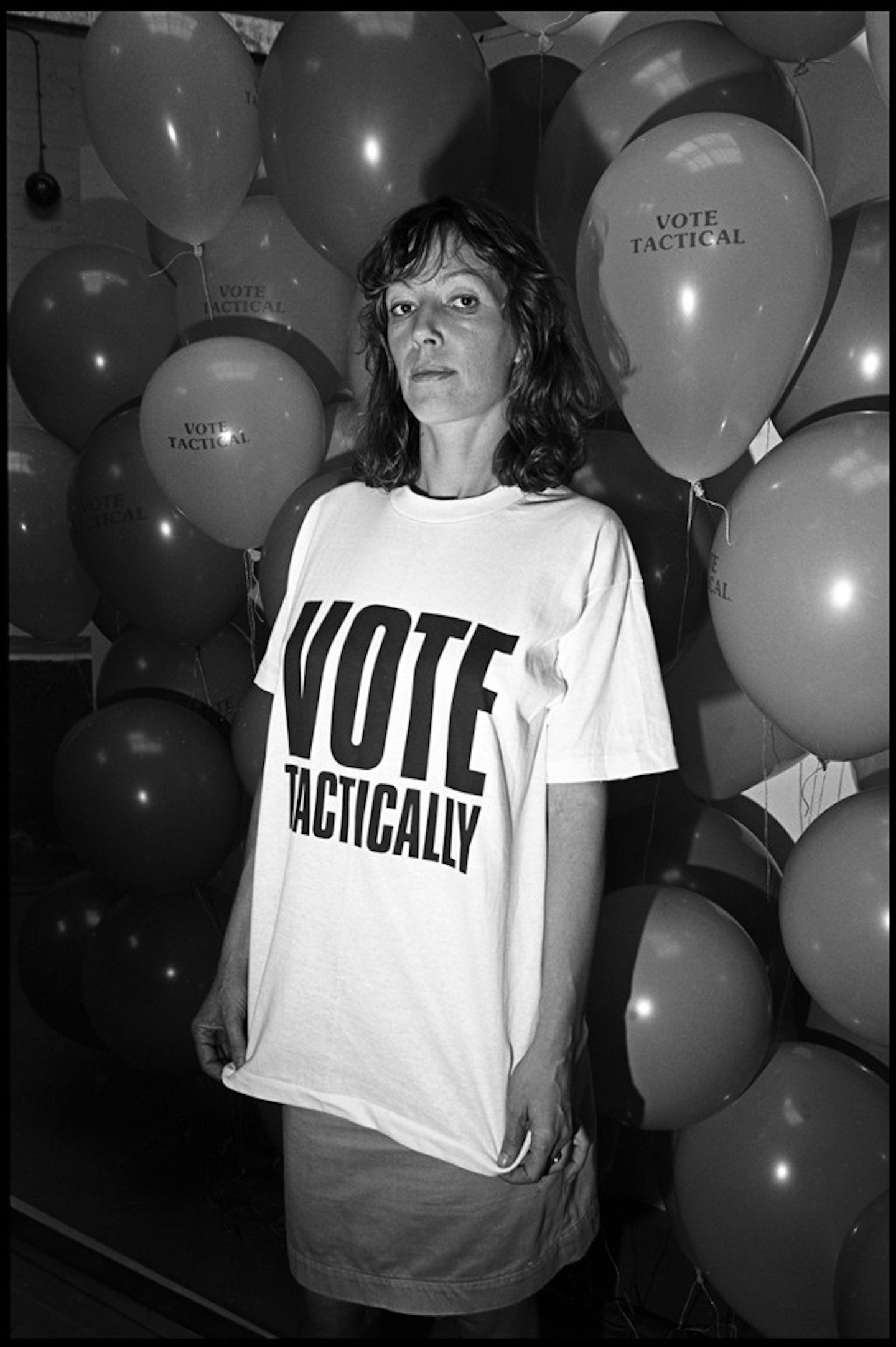

When trying to dissect the relationship between these two faculties of modern life it’s tempting to make a very tired case for the importance of fashion: what you wear makes a political statement. True, sometimes it does. Designers like Vivienne Westwood and Katherine Hamnett have certainly used their work and their catwalks to convey heavily charged and important political messages. Less overtly fashion can be political in the sense that it challenges norms and takes a sledge hammer to boundaries and smashes through them; designers like Meadham Kirchhoff who showcased tampon earrings one season for instance. However, citing such examples in an attempt to justify an interest in fashion unecessarily overcompicates things. It also feels like a shallow attempt to justify fashion by giving it a cerebral seriousness in order to legitimise it and, in doing so, implies that an interest in fashion does need to be justified. It doesn't. We all have to wear clothes. Study after study shows that those clothes affect the way others perceive us, particularly if we are women.So why? Can’t we just appreciate it for what it is, unapologetically? It’s self-expression.

That said, there are many legitimate criticisms of the fashion industry. Unrealistic body types, high wages for a few and exclusivity could very reasonably be targeted at football or, equally, the music industry. ‘Oh James, you’re interested in football aren’t you…?’ That doesn’t quite have the same cutting ring to it, does it? Why, I wonder? Because both football, like music is an approved heteronormative male interest. Did anybody bat an eyelid when Tony Blair threw a massive party at No. 10 for all the Britpop bands he happened to like and showered them in champagne?No.

I saw May interviewed when she was still Home Secretary at last year's Women In The Worldevent. The interviewer asked her about fashion, her taste in clothes and her preferences for designers. Her response was clear, if a little irritated:

‘I am a woman and I like clothes. I like shoes and I like clothes.’

‘I think one of the challenges for women in politics and in business and working life is actually to be ourselves.’

‘You know what, you can be clever and like clothes. You can have a career and like clothes.’

The room applauded her. If May was irked by the question, can we blame her? Women are caught between a rock and a hard place when it comes to this one. Society says that we must ‘invest’ in our outward appearance – not just in what we wear but in make up, hair removal, nails and teeth. An implicit value is placed on how women look to the extent that multiple studies confirm that men take women who dress up and wear make up more seriously in professional situations and even more likely to earn more. This is otherwise known as [the ‘make up tax’ {href='http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/08/the-makeup-tax/400478/' target='_blank' rel='noopener noreferrer'}see also women and high heels in the work place).

In politics it’s acceptable, if not an expected and unwritten part of the job description to be female and ‘fashionable’ if you are somebody’s wife – see Michelle Obama and Samantha Cameron. For MPs, Prime Ministers and potential Presidents there’s a tightrope to be walked and you’re much safer doing it in flats (but not trainers, that would be far too functional and suggest a lack of care).

The author Chiamanda Ngozi Adiche has written of how this extends to other professional spheres. It’s not just politics where women are scrutinized for and condemned based on their interest in what they wear. In an essay entitled 'Why Can’t Smart Women Love Fashion?' For Elle she wrote of how the problem manifests in academic communities, ‘women who wanted to be taken seriously were supposed to substantiate their seriousness with a studied indifference to appearance. If you spoke of fashion, it had to be with either apology or with the slightest of sneers.’

For a woman to be taken seriously her interest in fashion, if self-evident, must be accompanied with the appropriate amount of sardonic dismissal. You must look as though you care but act as though you don’t: something Theresa May seems to have perfected. ‘Of course I’m wearing nice shoes, you idiot’ is the answer she must give when quizzed, even if what she wants to say is ‘these? Yes! I’m so pleased you asked. I actually got them on sale and I really love them. When I’m going into Cabinet Office meetings they make me feel like anything is possible.’

Therein lies the double bind that women still face in 2016. You must invest in your appearance and look as though you’ve thought about it, but not too much and god forbid you look as though you’ve actively enjoyed getting dressed. If you do you’re liable to be dismissed as shallow or too ‘fashun’ which is code for frivolous and therefore fundamentally stupid and trivial.

Why do we continue to perpetuate to this obvious hypocrisy? Why do we allow people (often men but also other women) to make us feel ashamed for taking an active interest in fashion? After all, it goes without saying that fashion is more than clothes – it encompasses design, history, art, power dynamics, ethics, culture and craft. And, even if it did not comprise such diverse references – what is so wrong with wearing a leopard print shoe, a thigh high boot, a flared sleeve, a technicolour skirt or a vintage Prada dress for the simple reason that it makes you feel confident and brings you joy when you look in the mirror?

Years after my own ‘you like clothes, don’t you?’ incident’ I was working as a producer at one of the BBC’s flagship late night current affairs programmes. It was fashion week. An incredibly famous male presenter (who shall remain nameless) and infamous political interviewer was being briefed about the show that would air that evening. A female editor was talking to him about a potential segment about the economic value of the British fashion industry. He guffawed dismissively, ‘every year someone tries to get me to make the case that fashion is important. Every year we want to argue that it makes a big contribution to the economy. I’m just not convinced.’ My heart sank. This was coming from a man who had an impressive collection of ties and well-tailored suits and who I had, up unti this point, idolised professionally. Even he was not above falling for the obvious and inherent sexism of dimissing fashion and those who take an interest in it.

It’s more than enough to wear what you like for no other reason than because you want to but, nonetheless, to him I say this: according to the British Fashion Council’s most recent report fashion in the UK directly contributes nearly £21 billion to the economy. It also has an indirect economic impact, in encouraging spending in other industries, of over £16 billion. That’s a total economic impact of £37.2 billion which is no less than 2.7% of our nation’s GDP (when the study was conducted in 2009).

In a world where a woman is expected to show an interest in her appearance if she wants to be taken seriously, it’s high time we dropped the hypocrisy that an interest in appearance somehow also precludes a woman from being serious.

Like this? You might also be interested in:

Turns Out Kate Middleton Dresses Like An Emoji On The Reg** **

Follow Vicky on Twitter @Victoria_Spratt

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.